A righteous hero

Dr John Besemeres spoke at an Australian Institute of Polish Affairs event at the Polish consulate in Sydney, ahead of the commemoration of the liberation of Auschwitz and International Holocaust Remembrance Day on January 27. The following is an extract of his speech.

Dr John Besemeres spoke at an Australian Institute of Polish Affairs event at the Polish consulate in Sydney, ahead of the commemoration of the liberation of Auschwitz and International Holocaust Remembrance Day on January 27. The following is an extract of his speech.

FOR Australians of my generation, the lives of World War II heroes seem almost superhuman.

How did ordinary human beings set themselves, day after day, against the rampant, satanic evil that German occupation in World War II represented? And how did they maintain their resistance in the face of the almost equally inhuman force of Stalinism swamping them from the East?

Many people succumbed to the crushing pressures of the German-Soviet war in Europe by jettisoning moral values and doing terrible things that in a halfway normal life most would never have done.

Others responded with bleak resignation. Few had many options. Some, tragically, had no options whatsoever. And some, even many, succeeded in rising astonishingly to the occasion. Jan Karski was one such.

Karski was born in 1914 and brought up in a strongly Catholic family in a Lodz neighbourhood, where he had many Jewish friends.

After graduating in law and diplomacy at university, further study in a military academy, then a couple of years as a cadet diplomat, Karski found himself as a young officer in the Polish army, overwhelmed by the German blitzkrieg of September 1939.

When he was retreating to the East, Karski and his unit were captured by the Soviets entering Poland to claim their spoils from the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

Karski ingeniously avoided long-term Soviet captivity, where as an officer he would ultimately have been murdered by a bullet.

Next he escaped from a German cattle truck by persuading fellow prisoners to fling him from the moving train through a narrow eye-level aperture into a wintry landscape.

He survived the heavy fall and a barrage of bullets from German guards. Karski set off on foot for Warsaw, where he joined the nascent underground movement.

He was exposed to a high risk of the Gestapo arresting him daily, as some of his family members had already discovered.

He became an international courier for the underground, dispatched on hazardous, circuitous routes to France and later London, where the emergent Polish government in exile was located.

On the second of these, he was betrayed to the Gestapo in Slovakia.

After repeated bashings under interrogation by both the Gestapo and the SS, fearing he might reveal damaging information about the underground, he tried to take his own life but the Germans sent him to hospital and kept him alive because they believed he had valuable intelligence.

The underground decided that Karski and his secrets would have to be rescued.

Thirty hospital employees were later killed as a result of the successful rescue.

He was deployed straight back into the underground and he tried to save a Jewish couple in Warsaw by relocating them to the countryside.

With help from Jewish underground leaders, he also made covert visits to the Warsaw Ghetto and a German death camp, which affected him deeply.

In late 1942, Karski was chosen for a high-level visit to the government in exile in London.

The main priority was to explain to the Allies the full horror of the unfolding mass murder of Europe’s Jews in occupied Poland.

In London, he had meetings with Polish [Prime Minister] General Sikorski, Polish President Raczkiewicz and British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden.

Following the meeting Raczkiewicz wrote a strong letter to Pope Pius XII and pleaded with him to publicly denounce the Germans’ crimes against the Jews, but without much effect.

Based in part on Karski’s testimony and smuggled materials, the government prepared a note on the “Mass Extermination of Jews in German-Occupied Poland”, presented to the Allies by Polish Foreign Minister Raczynski on December 10, 1942.

Seven days later the Allies issued a declaration condemning the Germans’ murder of the Jews, but little of substance changed as a result.

In 1943, Karski took his message to the United States.

He saw many senior figures, including President Roosevelt, who spoke with Karski for over an hour.

He also met leading American Jews, notably Rabbi Stephen Wise and Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, who declared that he found Karski’s graphic testimony unbelievable.

But, Karski’s mission to the US ended in failure.

After decades of anguished silence, he was drawn again, reluctantly, into public discussion of the Holocaust, initially by Claude Lanzmann, during the making of Shoah.

Then in 1981, Elie Wiesel also “discovered” Karski when organising a Washington conference on the Holocaust, and managed to persuade him to speak about it in public for the first time.

This led to a more general public recognition of his efforts internationally, including in Israel.

At Wiesel’s conference, Karski struck an eloquent note of bitter elegy: “The Lord assigned me a role to speak and write during the war, when – as it seemed to me – it might help. It did not,” Karski said.

“Furthermore when the war came to an end I learnt that the governments, the leaders, the scholars, the writers did not know what had been happening to the Jews … The murder of six million innocents was a secret.

“I am a practising Catholic. Although I am not a heretic, still my faith tells me the second original sin has been committed: through commission or omission, or self-imposed ignorance, or insensitivity, or self-interest, or hypocrisy, or heartless rationalisation.

“This sin will haunt humanity to the end of time. It does haunt me. And I want it to be so.”

Dr John Besemeres is the adjunct fellow at the Centre for European Studies at the Australian National University in Canberra. The commemoration of the liberation of Auschwitz and International Holocaust Memorial Day will be at 11am on January 27 at Council House in Woollahra. For more information, call (02) 9360 7999.

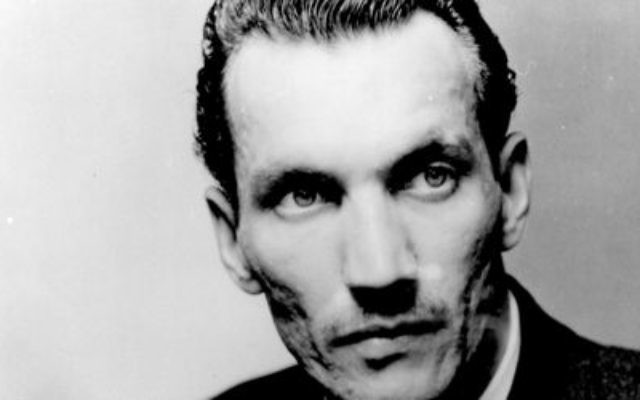

Pictured is Jan Karski.

comments