TO describe Lisa Jackson Pulver as an “inspiration” seems overly simplis- tic, a trite and lacklustre attempt at neatly containing her and her many triumphs to a neat box.

Some people cannot be so easily contained – and it is difficult to find one word that truly encapsulates all that she is.

So here are a few: Resilient domestic abuse survivor. Ambitious nurse. Social justice warrior. Progressive epidemiologist. Committed professor. Resolute activist.

A Jewish and Wiradjuri Koori woman.

In fact, Lisa Jackson Pulver is the first known Aboriginal person to have received a PhD in medicine.

And with a Member of the Order of Australia in tow, she holds the position of Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Indigenous Strategy and Services, at the University of Sydney.

But in our early morning Zoom meeting, she is just Lisa. Unassuming, in a black turtleneck, she potters around the kitchen of her office, making a cup of tea. She is chatty, familiar and down to earth, as she searches for a quiet space for our conversation, settling upon a modest shared office nook.

THE firstborn of three children, Lisa was raised in the Sydney suburb of Revesby. While both parents were Aboriginal, Lisa says that they never really identified in that way.

“We were in an area where there are a lot of other fair-skinned Aboriginal families and a lot of migrant families, Greek families,” her voice trails off.

“Everyone did look a bit different from each other anyhow, so it wasn’t actually a deal then. We had a lot of Aboriginal families living around us and they all knew who we were, and we all knew who they were. But it was never a thing.”

Lisa believed her mother was a descendant of a “Maori princess” – lineage that into her mid-30s, Lisa would discover to be more fiction than fact. But when she confronted her mother, she was met with the response, “Well, it’s better than saying you’re an Aboriginal.”

Lisa recalls an upbringing tainted by “extreme violence and extreme pain of people self-medicating”. Her father was a returned World War II veteran “badly damaged by his experience”, and her mother was grieving the loss of her father in the same war. Lisa’s father drank to excess and gambled, betting on “anything that had legs or eyes”.

“There was quite a lot of unspeakable stuff that happened… But for me, growing up in that environment, you become very resilient and very, very able to survive anything.”

And at age 14, Lisa’s resilience was tested on another level.

On learning that Lisa’s young boyfriend was waiting for her around the corner from the family home, her father reached for his shotgun, in a drunken rage.

“He started waving it around the house and mum was yelling at him, saying, ‘Go on, shoot it, you gutless wonder!’”

“Then he aimed it straight at me, and I could see his fingers start to move and I just bolted out the door and ran up the street as fast as I could go, and I heard it go off behind me and I heard something smash.”

Lisa did not return home.

“The bashings you can sort of cope with because you can wriggle out of the way fairly quickly, or just get one hit, and then run, but someone with a knife or a gun … that just changes it.”

From that moment, Lisa did not see her family for more than 15 years.

A homeless teenager, she slept in the back of cars, and on the roofs of buildings, relying on the generosity of strangers who occasionally helped her on her way. Lisa changed her look, appearing more boy-like, “a mechanism of safety on the streets”. She ended up at an old boarding house for men in Potts Point, where she offered to help clean toilets and the kitchen in exchange for a room of her own. There she met Alice, an outreach Catholic nun who would change her path forever.

“You’re better than this,” she told Lisa. “You can’t live here forever. What are you going to do?”

Realising she liked to help people, Alice encouraged Lisa to enrol in technical college, to complete a transition program to finish her secondary schooling, and undertake nursing.

She did, at Lidcombe Hospital

Tells Lisa, “Frankly, I’ve just been smart enough to be able to take others’ wisdom and be guided by it.”

After gaining her qualifications and working as a nurse for a time, she fell in love and ran away with an artist, working with him in a small screen-printing business. When the romance faded, Lisa realised she wanted something more. Drawn towards the study of neurolinguistics, she curiously enrolled in a couple of weekend workshops.

Before long, Lisa realised that she wanted to become a brain surgeon.

“The only problem is that you had to do medicine first.”

“I HAD more front than David Jones. Absolute chutzpah!” she reflects, shaking her head. With the help of a friend, Lisa penned a letter to the University of Sydney and “just gave them this big, long story about my desires and dreams” in the hope she would gain entry into medicine.

And she did. In 1992, she was offered a place – and was the only Koori in the class.

But Lisa says that with no idea how to apply herself to full-time study, and without any financial resources, she lived on a diet of rice, trying to work to support herself and meet the ever-pressing demand of rent.

She failed first year, and repeated it. She battled through, but by third year, at the advice of a trusted professor, she deferred medicine, opting to study a Master of Public Health part-time.

Finding her stride – and a passion for Indigenous health -– following the Masters, Lisa completed a PhD in medicine, the first known Aboriginal person to do so.

“Gee whiz, that took a while, didn’t it?” she says in bemusement.

“Since its first graduation ceremony in 1859, this university has graduated more than 500,000 people, yet our first known Aboriginal graduate was the 1970s [and] 2003 was the first PhD in medicine [received by a Koori] in this place. Hello! 2003?!”

“So, you have this minuscule proportion of Australia’s first peoples graduating. That’s shocking and we have to work hard to change it.”

Lisa acknowledges the unique challenges faced by young Indigenous students, most of whom have not had the privilege of private school education and the advantage of economic support from home. Indeed, it is an issue that drove her to action following a chance meeting with then president of the board of Shalom College, Ilona Lee. With the involvement of college master Dr Hilton Immerman, the seed of an idea blossomed into the Shalom Gamarada Indigenous Scholarship, assisting Indigenous students with the almost insurmountable problems of finding a safe, affordable place to live near UNSW while studying.

Sixteen years later, more than 50 graduates have now completed the program, forming one quarter of Aboriginal doctors across Australia.

“It’s the hard work of Ilona, the board of trustees of the program and of the Jewish community … just generosity.”

In improving the plight of Indigenous Australians, Lisa implores, “The biggest help that we can do is to engage with the opportunities in every quarter… Enable that door to be opened.”

DESCRIBING herself as “always a bit of a spiritual being”, Lisa believes that Aboriginal spirituality does not preclude faith. While she was raised as Christian, as she grew older, Lisa began to explore other religions – “and when I fell upon Judaism, it felt like a natural fit”.

Addressing an online JNForever event late last year, Lisa told a story of finding an older Chasidic man wandering around Surry Hills, appearing to be lost. He couldn’t speak a word of English, and so she beckoned him to join her as she tried to help him. Lisa brought him to her friend’s house nearby, who happened to be Jewish. There, they conversed in Yiddish, and Lisa’s friend was able to direct him to his destination. Incredibly thankful, the man left Lisa and her friend with a set of leather-bound books – the Torah, and its interpretations and commentary.

“I thought that was really interesting, and so, I started looking at Kabbalah and did a whole stack of readings,” shared Lisa.

She later met her Jewish husband-to-be Mark Pulver, and she quietly started taking herself off to shule on Friday evenings.

In 2004, Lisa converted to Judaism and wedded Mark in an Orthodox ceremony.

For Lisa, the interplay of her Aboriginal spirituality and Jewish identity is linked by one central notion, “Tikkun Olam”.

“It is probably the most important principle of practice in Judaism, which is so aligned to Aboriginal spirituality. It’s the same thing.

“Go forth and multiply – and once you’ve done that, make the joint a better place.

“I think if you look at any culture around the world, you always see this idea about paying respect to your ancestors, paying respect to God, paying respect to country, the land and the trees. It’s about recognising that you are very little, in this big, big hole. And without that big, big hole, you’re nothing! I love that.”

By 2010, she became the president of Newtown Synagogue – the first woman to hold the role. But Lisa is not afraid to push boundaries.

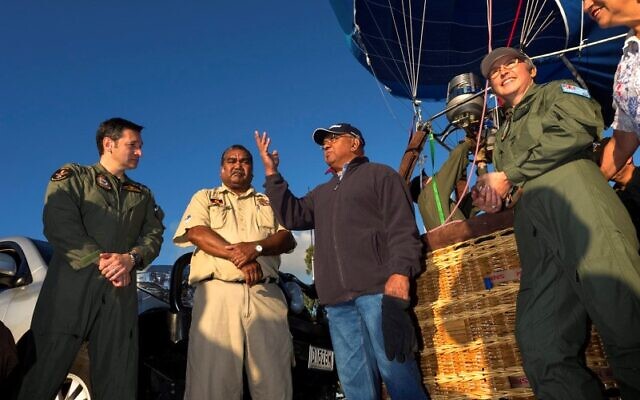

She is also a reservist in the Royal Australian Air Force, a position she was turned away from twice before being finally accepted.

Her tenaciousness extends into her activism, climbing and chaining herself to a tree on the Gordon River in opposition to the building of the Franklin Dam in the early 1980s.

“Australia has been a magnificent place and nurtured its people – no matter what your belief systems are – my grandmother would say, from the beginning of time … This is the oldest continuous surviving culture in the history of the world – that means the people were doing something right; Living in accordance with the laws of the land, recognising that you don’t eat all the critters that are there, that you have rules around that, that you observe seasons.

“That was history that was handed on, through dance, ceremony and song. This has always been a place where people have been able to live in harmony with the environment, and it’s a very, very long story.”

Reflecting on the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement last year, Lisa applauds the conversation it has created around colour and racism. She recalled the George Floyd incident – and the identical words in 2015 of David Dungay Junior, the Aboriginal man who cried, “I can’t breathe” while being held face-down by six prison guards in his NSW prison cell, and later died.

“It was on the news, and they took no action. We as a society should hang our heads in shame,” she laments.

Indigenous Australians are just three per cent of Australia’s population, and yet they make up more than a quarter of the country’s total prison population, “a huge problem”, says Lisa.

“If we get shocked about what happens in America, please look at what’s happening in our own backyard because it’s very real. It happens here every day.

“Black lives matter. When it comes to the kind of close-eyedness that people have in this nation against Australia’s First Nation people, we have a long way to go.”

CASUALLY slouched across the desk where she sits, Lisa contemplates the path thus far, and the adversity that she has fashioned into achievement.

“It’s just one foot after the other, and keep breathing.

“University gave me the opportunity. I may be considered a failed medical student, but actually I’m quite proud of that because it got me to where I really wanted to be, which is where I am now, I suppose.”

She offers one final thought, “One of the things that I say to people, is that if you see an opportunity and if it makes you feel uncomfortable because you’re worried about stretching yourself, then by all means, take it.

“It’s made for you.”

If you are in immediate danger from domestic violence, call 000. For additional support, call Jewish Care Victoria on (03) 8517 5999 or JewishCare NSW on 1300 133 660; 1800 RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or Safe Steps on 1800 015 188.

For more information on the Shalom Gamarada Indigenous Residential Scholarship Program, visit shalomgamarada.org.

comments