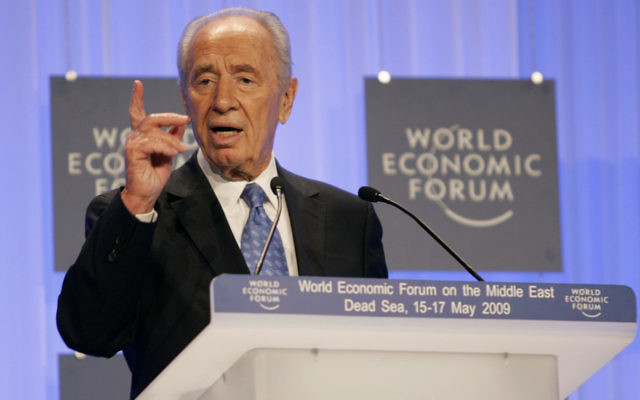

The hawk who became a dove

SHIMON Peres was a Pole who became an icon of Israel. He was a hawk who became the country’s most famous dove. He was a man who struggled for years to endear himself to the public – and finally became a national treasure.

SHIMON Peres was a Pole who became an icon of Israel. He was a hawk who became the country’s most famous dove. He was a man who struggled for years to endear himself to the public – and finally became a national treasure.

A thinker and dreamer who lacked the hands-on military experience and hard-hitting style that normally triumphs in Israeli politics, on each of the five occasions he went to voters as Labour’s candidate for Prime Minister they never gave him the endorsement he needed.

He did have two short stints as Prime Minister – one from 1984 to 1986 when he had to share the job in a rotation agreement with Yitzhak Shamir, and another when he inherited the job from Yitzhak Rabin after his 1995 assassination. But his dream of being elected with a full mandate to take the country in new directions never came to pass.

He couldn’t accept this. Even after almost 50 years in the Knesset, and after serving in virtually every government position, he still had an as-yet unfulfilled desire to lead. He had been the defence minister who dispatched Israeli commandos for the heroic rescue at Entebbe; he had built the country’s defences of his nation from just before statehood to the early days of Israel, and then transformed it into a nuclear power; and he had saved Israel’s economy from the hyperinflation of the early 1980s. But he felt that he had more to give.

Peres set his sights on the role of president, which is filled by a vote of Knesset members not the public. His first bid for this job, in 2000, failed when Likud’s Moshe Katsav won, but he succeeded in 2007. By this point he had left Labour for Kadima, and as Kadima was the largest party in Knesset, it could help propel Peres to victory.

Installed at the President’s Residence, Peres came into his own as the beloved leader that he so wanted to be. He gave the presidency back its dignity, after his predecessor Katsav had resigned under a cloud of suspected sexual misconduct – to be later found guilty of rape and sexual misconduct, and imprisoned.

As president, Peres’ unflattering exploits such as the “dirty trick” of 1990, in which he brought down the national unity government after trying to take control of it, seemed a lifetime away. People who met him found it hard to imagine that this was the same man who had a long and bitter rivalry with Yitzhak Rabin. He became the epitome of charm, gentlemanly conduct, and wisdom which he enthusiastically shared with his subjects and with world leaders.

In a country that was becoming increasingly sceptical about the chances of a peace agreement with the Palestinians, Peres took every opportunity as President to outline the set of beliefs which led him to start the Oslo peace process with the Palestinians back in the 1990s. After all, he had been the driving force behind the Oslo process. As president his voice was an important morale boost to the Israeli peace camp during its troubled times, and if it had not been so audible, always repeating the virtues of negotiations and tying Israel’s image on the world stage to its search for peace, Israeli doves would likely be in a far weaker position than they are today.

As Israel faced growing isolation internationally, Peres’ charm, erudition, and credentials as a dove and a humanitarian went a long way. So did his technophile nature, as people found his enthusiasm for Israeli technology infectious.

Foreign officials, diplomats, actors and other opinion shapers could not help but like him, and as the crowd at his funeral will show, he commanded their respect. Some related to Israel more favourably based on their dealings with him, viewing him as embodying Israel as it can be. This went a long way to shape attitudes towards the Jewish State.

Peres’ presidency came with a personal cost. His wife Sonia had always disliked public life. She stayed in the shadows, and wanted, at least in old age, for her husband to have a more normal existence. When it became clear that even in his eighties he was determined to serve more, they separated.

He later recalled the conversation where they decided to live apart. “‘‘Look,’ I said to her, ‘I have served the country, the people, all my life. This is what gives my life content, I don’t even know what time off is, for me time off is like dying. I will die if I don’t [stand for president].

“She said to me: ‘You’ve done enough. There are other people who can serve the country now.’” Peres still felt the call and “we decided to go our separate ways.” The couple’s children – Tsvia Walden, Yoni Peres and Chemi Peres – kept up good relationships with their father after the separation.

Peres’ name is today synonymous with the peace camp, and part of his legacy is the Peres Center for Peace. But it was more than halfway through his life that he was converted to a dovish path. He was part of the Labour Party when Israel conquered the West Bank and Gaza in 1967, but was unimpressed by the idea of withdrawal and a peace treaty. He was Defence Minister during key early moments of the settlement movement. Peres supported the movement, and helped it to create facts on the ground.

His transformation came in the late 1970s and early 1980s. For him, watching Israel make a peace agreement with Egypt was a sign of what was achievable. By the mid-1980s he was well and truly convinced that peace talks were the way forwards, and by 1987 he was starting to secretly meet Arab leaders, in talks that were the forerunner of the Oslo process.

And so the Polish Szymon Perski, who arrived in British-ruled Palestine as an 11-year-old boy, who became close confidant to David Ben-Gurion and helped give the young Israel the ability to defend itself, embarked on the path that he was desperate to complete — the path of peace. His vision earned him the Nobel Peace Prize, propelled him to the presidency, and turned him from a well-known politician into the Israeli icon who people are remembering today.

NATHAN JEFFAY

comments