Paying tribute to the Agia Zoni

On the eve of World War II, 459 Jewish refugees escaped Europe for Palestine on a ship called the Agia Zoni. The history of the voyage is not well-known; however, the Australian grandsons of two of its organisers aim to change that. Gareth Narunsky reports:

On the eve of World War II, 459 Jewish refugees escaped Europe for Palestine on a ship called the Agia Zoni. The history of the voyage is not well-known; however, the Australian grandsons of two of its organisers aim to change that. Gareth Narunsky reports:

THE writing was well and truly on the wall for the Jews of Europe by the time the Jewish Agency in Zurich decided to organise a ship from Fiume (now in Croatia and known as Rijeka) to Palestine in February 1939.

The horrors of Kristallnacht in November 1938 were still fresh, while many Jews were already suffering in German labour camps.

The plan was to bring Jews from the labour camps, as well as from France, Switzerland, Austria and Italy by train to the Port of Fiume. Once there they would board a ship seemingly headed for Shanghai, but in actuality, bound for Palestine.

Among the many organisers who enabled the voyage were Alfons Goldmann, an employee of the Italian Tourism Bureau (CIT) who had fled Nazi-occupied Vienna, and Max (Sami) Wassner, a proud Polish-born Jew who was at one time president of the Austrian Haganah.

Goldmann kept a diary, written in German, in which he recorded the whole affair in detail. That diary would one day be handed down to his son Tom Goldman and grandson David.

“Alfons never spoke about the Agia Zoni, and in fact we didn’t know he had written his journal until after he passed,” David Goldman told The AJN.

“There was some conversation about his experiences in 1939 and beyond; however, it wasn’t until I had the diary translated – after he died – by the Goethe Institute in Sydney that the whole story came out.”

That story is fraught with setbacks.

Upon arrival in Fiume, the group was intercepted by police and had their passports seized. The organisers learned their ship was not coming.

The authorities offered Goldmann another ship, which needed to be refurbished at a cost of 800 pounds, with the work taking three weeks. He, along with another organiser, declined the offer, subsequently writing in his diary that had he known the mission would end up costing even more and taking longer, he would have accepted.

The group was granted visas to stay in Fiume until their departure, but they needed somewhere to stay.

Wassner had negotiated with the owner of the Hotel Quisisana, which was closed for the winter, for the group to stay until a new ship could be found.

After a few days, and at considerable expense, the organisers booked another ship, the Agia Zoni. Goldmann wrote in his diary that “ the ship was described to us as very sea- worthy and comfortable … it would comfortably offer space for 700 persons”. Wassner helped to raise additional funds to secure the ship.

When it arrived, however, it was far from as described – a small freighter commissioned to carry only 55 people.

With the authorities not allowing the group to stay at Fiume any longer, it was eventually agreed after yet more negotiations – this time aided by an influential local lawyer – that the ship be could be converted, at a cost of 1100 pounds, to carry 350 passengers.

Yet more money was to be demanded by the ship’s owner and captain before it was finally ready and passengers could board.

The ship set sail on March 17 carrying 459 passengers – some singing the Hatikvah as it left port – and 35 crew.

The passengers were to face further trials on the journey, with the corrupt crew exploiting them for all their money and possessions, and the captain repeatedly threatening to turn back unless given more money. Finally on April 21, they arrived in Palestine.

An unknown passenger kept a diary of the voyage which was sent to Alfons Goldmann.

GOLDMANN and Wassner themselves did not travel on the ship. After its departure, CIT sent Goldmann to its new office in England. He volunteered for the British Army in November 1939 and worked from May 1940 in the bomb disposal and transport control units.

He served in the rescue of the Allied troops at Dunkirk and landed with his fellow troops in Europe on D-Day. His children Peter and Tom Goldman were born during his years of service.

He was discharged from the army in November 1946 and sailed to Australia with his wife and children four years later.

Wassner married his bride Rachel in Zurich and the couple escaped Europe on the “Oronsay”, one of the last ships to depart before war broke out.

His intention was to change ships in Aden, Yemen and go to Palestine, but war was declared while the ship was in port and British intelligence would not allow this. The ship continued on to Australia, where they would settle.

Alfons Goldman (he dropped the extra “n” while in England) passed away in 1986, shortly after the bar mitzvah of his grandson, David. “I remember being so thankful that he was there and shared this occasion with me and my family,” David Goldman said.

“I just wish I would have had more time with him to hear his stories.”

In a way, Goldman would get that opportunity, albeit in written form rather than from the man himself. “I have always been fascinated by history so when I found out there was an opportunity for me to have this diary translated, I was keen. I knew there was a phenomenal story to tell,” he said.

As Goldman’s interest in his grandfather’s deeds was getting piqued, sotoo was the interest of Wassner’s grandson, solicitor Glen Cremer.

“I was very close with my grandfather,” Cremer told The AJN. “I used to help him in his shop while I was at school and university, and I learnt a lot from him and about him in these years.”

One thing Cremer didn’t know a lot about, however, was the Agia Zoni.

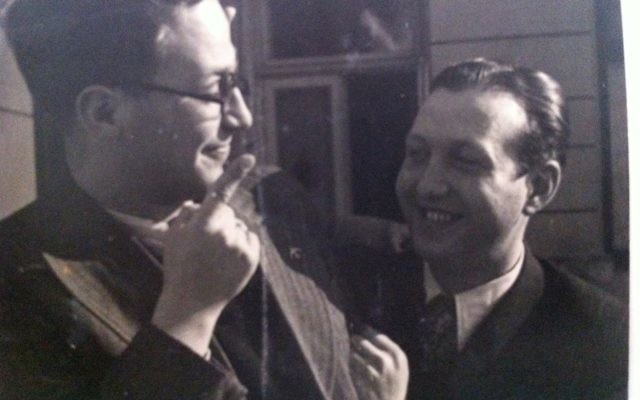

“Occasionally he would mention how he helped get people to Israel but mainly I heard [the story] through my grandmother Rachel after he passed away in 1995, and through a photographic record which was put together by a friend of his on his 50th wedding anniversary. The photos clearly show Max with the other organisers, with the financial backers, with the [Quisisana] hotel owner in Abazzia,” he said.

Cremer was looking through the album with his mother one day and she pointed out Alfons Goldman, mentioning that she knew his son, Tom. “Tom put me onto David who had a similar interest in reviving the story.”

Goldman said: “Glen’s parents were in our office – and my dad called me in to meet them. They then introduced me to Glen, and we both wanted to get the story out … It was great timing.”

The two grandsons have spent several years developing a website to raise awareness of the Agia Zoni as a tribute to their inspirational ancestors.

“We created the website so that we could have a perpetual memory of our grandfathers, to honour them, for a historical record and hopefully as an inspirational story,” Cremer said.

“We also thought perhaps one day we could reunite families who came out on this trip, and finally raise funds in support of Israel to reflect the good work and sacrifices of Max [a passionate Zionist and JNF activist during his lifetime] and Alfons.”

Added Goldman: “We are doing this for our grandfathers’ memory and of course our family legacy. We don’t want this to be forgotten or hidden.”

In an amazing turn of events, the Primo Levi Centre found the website and contacted the pair.

“It was fantastic that Primo Levi found the website … and provided all the historical facts which support the story,” Goldman said. “Some of my grandfather’s diary actually contradicts what was once known to be fact.”

After years of work, Goldman and Cremer are ready to share the website with the community and the world.

“It’s simply a story that needs to be told,” Goldman said, noting that the website is merely the beginning.

“My hope would be to meet families of [people who were] on the boat and to continue to build the story.

“We already have had someone contact us [about that] and it would be great to meet more and have an event in Israel in memory for all.”

They also hope to one day release a book in addition to seeing exhibits established at the Sydney Jewish Museum and Yad Vashem.

“I do believe it will be a work in progress for many years to come,” Goldman said.

View the website at www.aliyabet.com.

comments