The smart way to chase yield

IT is a challenging time for investors, with global trade tensions and Brexit unresolved, equities at stretched valuations and Australian interest rates below 1 per cent, which are historically unprecedented lows and likely to decline even further.

Global gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to grow at a sluggish, although not recessionary, 2.6 per cent this year and next, with growth momentum expected to improve throughout the course of next year.

The questions on everyone’s lips are where to find an appropriate yield and what risk should you be prepared to take to achieve it?

Investors who rely on the income generated from their portfolios are in a difficult situation.

Cash is an unattractive place to be.

Also, it must be accepted that the yield on bonds is low and, given the Reserve Bank of Australia’s guidance, likely to stay that way for what could be years.

The temptation is to add risk to the portfolio in the form of equities or lower rated bond and bond-like investments to push the yield up.

However, the experience from the global financial crisis (GFC) is that a major risk-off event, which is when investors attempt to reduce risk by selling risky investments, is brutal on these asset classes.

In particular, funds wrapped around illiquid debt such as higher risk corporate and mezzanine debt froze up and stopped meeting redemptions.

We therefore tell our clients to manage to a “risk budget”.

The asset allocation will reflect that risk budget and is easier to target than a particular return.

Do not be turned off bonds by the low yield – you will be glad you have them in a sell-off.

A sensible portfolio will include alternative investments such as hedge funds, private equity and property.

The starting point for our portfolios is allocating about 20 per cent to listed and unlisted alternatives. For some people however, there are better options.

In terms of volatility, unlisted investments in private equity, infrastructure, direct property and hedge funds are a better option than simply loading up on equities for income.

The disadvantages for these asset classes is often lack of knowledge, liquidity and the ability to access them with small amounts of capital.

However, there are ways to do this with the right advice and network.

An analysis of the asset allocation of the top 10 performing industry super funds for 2018 by Chant West shows a total allocation of 36 per cent to listed and unlisted alternatives, with a little over a half of that in unlisted assets.

The Future Fund has an even higher allocation.

However, keep in mind that industry funds and the Future Fund do not have any issues with liquidity.

Unlike the average investor, they can lock a larger proportion of their investments away for years.

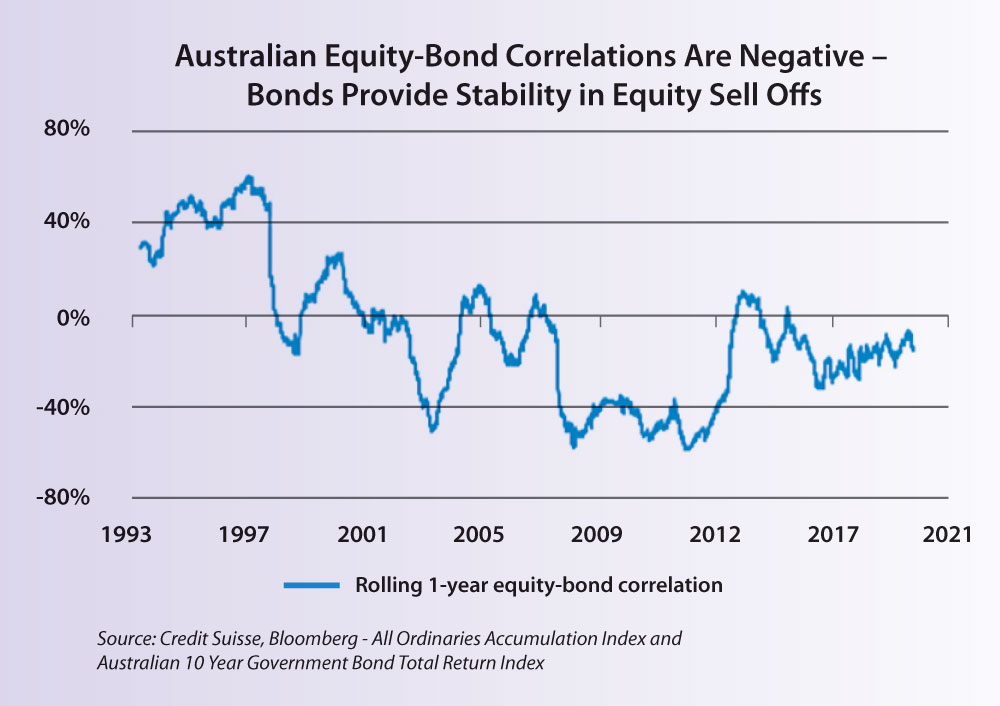

Regarding bonds, they are not in a portfolio just for yield.

They also provide portfolio stability during equity market sell-offs.

Thus, we would be careful going up the risk curve without understanding the increased drawdown your portfolio will experience in a crisis.

Their low yields don’t mean that bonds will fail to protect you in a risk-off event.

For example, the experience of Switzerland shows that even with negative official cash rates since 2011 – and negative yields on government bonds since 2015 – stock market sell-offs over this period have seen positive returns on bonds on almost every occasion.

People also shouldn’t discount Australian bonds for yield just yet.

Yes, the often-quoted 10-year Australian government bond yield at 1 per cent is low – but that’s only part of the story.

The inclusion of state-government and corporate bonds will enhance the yield on offer.

Investment grade bonds issued by non-cyclical companies have attractive qualities.

Aussie-dollar issues from government-supported agencies also provide some yield gain.

Investors can also consider credit from low-risk issuers that is further down the capital structure and so attracts a higher yield.

For example, the big four banks are currently issuing tier two subordinated debt at a significantly better yield to their own senior debt. Same company, better yield.

Managers of Aussie-bond funds are well aware of this.

Australian equities provide an attractive yield relative to bonds but are obviously riskier.

This can be reduced by looking at less cyclical sectors such as infrastructure, consumer staples and A-REITs (Australian real estate investment trusts, which are ASX-listed companies that own real-estate assets).

In A-REITs, our portfolios are biased towards industrial and office and away from retail. A-REITs have been the best-performing sector this year and yet the spread between the A-REITs yields and 10-year bond rate has increased, pointing to valuation support.

Likewise, the forward yield of the broad Australian market (as represented by the ASX 200) at 4.3 per cent looks attractive relative to low bond yields.

And their associated franking credits make them even more attractive on an after-tax basis.

In truth, a preoccupation with inflating the income from a portfolio in a low-yield environment can lead to a poor risk/return outcome.

But a diversified multi-asset-class portfolio will generate a lower – but still reasonable – level of yield while smoothing returns.

With such a portfolio, an investor can also realise profits if needed – an approach that can get lost with a blunt focus on yield.

Andrew McAuley is Credit Suisse Australia Private Banking’s chief investment officer.

The AJN recommends that readers seek independent financial advice.

Get The AJN Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

comments