What’s on the table in Donald’s deal?

'[The deal] demonstrates to the Palestinian leadership that continuing to say no to every peace offer will have a cost – with less offered next time around, rather than more'.

UNITED States President Donald Trump’s long-awaited “deal of the century” peace plan will not satisfy both sides’ maximalist positions and fudges some of the detail, but does provide some innovative proposals to ensure Israel’s security needs.

The plan’s subtext is that time is not on the Palestinians’ side and their leaders need to negotiate now.

The vision provides for a Palestinian state in four years’ time that is smaller than what their leaders rejected in 2000/01 and 2008 and concretises the economic benefits of peace through a US$50 billion fund. It is predicated on ensuring Israel’s security and its future as a Jewish state.

As Trump said, “We will never ask Israel to compromise its security.”

Addressing the security coin’s flipside, Trump said, “We are asking the Palestinians to meet the challenges of peaceful coexistence,” which requires ending “the malign activities” of Hamas and Islamic Jihad, “ending incitement” against Israel and “halting financial compensation to terrorists”.

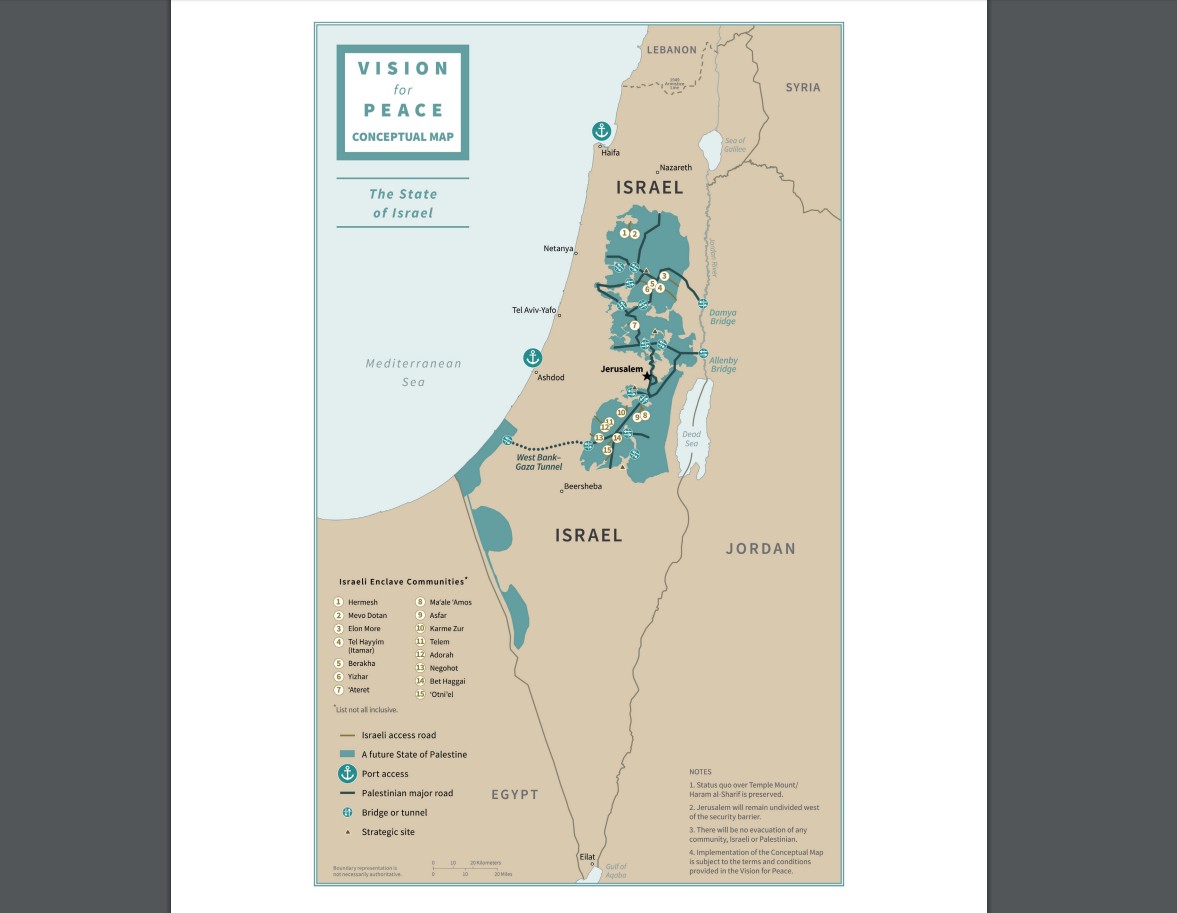

The plan provides a map for “a demilitarised Palestinian state living peacefully alongside Israel, with Israel retaining security responsibility west of the Jordan River”, Palestinian access to the ports of Haifa and Ashdod and a land corridor linking Gaza and the West Bank.

Israel will keep the strategic Jordan Valley, and will not have to evacuate any settlements.

Israel also has to agree to a four-year freeze on settlement expansion.

It calls for recognition of Israel as the nation state of the Jewish people – a concept which Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas has repeatedly rejected.

The plan also closes the door on Palestinian dreams of flooding Israel with refugees, giving them the option to “live within the future State of Palestine, integrate into the countries where they currently live, or resettle in a third country”.

Palestinian interests in Jerusalem have been addressed by offering them a capital in east Jerusalem neighbourhoods outside the security barrier.

The plan itself is reminiscent of the contours for peace that Israeli PM Yitzhak Rabin proposed in the Knesset in 1995, shortly before his assassination: “a Palestinian entity”, no “return to the 4 June 1967 lines”, a united Jerusalem under Israeli control and “the security border of the State of Israel … located in the Jordan Valley”.

Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu and opposition leader Benny Gantz have both accepted the plan as the basis for negotiations.

As in the past three years of the Trump Administration’s announcements on the issue, or indeed, at every opportunity to create a Palestinian state since the 1930s, the Palestinian leadership predictably and furiously rejected the plan.

A White House fact sheet addressed this; “If the Palestinians have concerns with this Vision, they should bring them forth in the context of good-faith negotiations with the Israelis.”

Trump is hoping the plan will be backed by European countries and responsible Sunni Arab leaders who are interested in maintaining their partnership with Israel and not just solidarity with the Palestinians.

The deal’s prospects for success remain hostage to whether Palestinian leaders will end 100 years of opposing Jewish self-determination in their ancestral homeland and put an end to the terrorism that has accompanied that hard-line stance.

Given genocidal Hamas still controls Gaza and the PA has rejected far more generous past offers of a state, this looks highly unlikely.

However, even in the face of Palestinian rejectionism, the plan has two important virtues. It offers a fresh take on what an Israeli–Palestinian peace might look like, challenging past paradigms which look increasingly out of date. And it demonstrates to the Palestinian leadership that continuing to say no to every peace offer will have a cost – with less offered next time around, rather than more.

Allon Lee is a senior policy analyst at the Australia/Israel & Jewish Affairs Council.

Get The AJN Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

comments