Why much-loved shares can fall out of favour

By ADam spicer

A “market darling” can be thought of as a high-flying growth stock that attracts the attention of the investment world and invariably trades at a ludicrous and unsustainable valuation. While riding the wave of a current market darling might make you money on the way up, market darlings over history have proven a costly lesson for investors.

This is illustrated by esteemed value-investor James O’Shaughnessy’s findings in What Works On Wall Street, where he analyses a raft of objective financial ratios dating back to 1926 on the US market.

His findings show that if an investor was to buy Wall Street’s current market darlings with the richest valuations (e.g. high price-to-earnings ratios, price-to cash flow and price-to-sales ratios), this is one of the worst strategies you can do over long periods of time, and over many market cycles.

O’Shaughnessy contends, “Our very human nature leads us to believe that we live in unique times, in which lessons from the past no longer apply. Generation after generation has shared this outlook, and by ignoring the lessons of the past each generation has repeated the same mistakes of its predecessors.”

The US Nasdaq index is up circa 450 per cent over the past decade. The market darlings of the Nasdaq comprise the FANGs stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google-owner Alphabet), which at the time of writing in late November are all down 20 per cent or more from their one-year high.

Make no mistake about it, these top-tier businesses generate billions in revenues and profits. However, looking at these businesses objectively – in terms of the future growth rates required to justify some of the current valuations – the returns will have to be extraordinary.

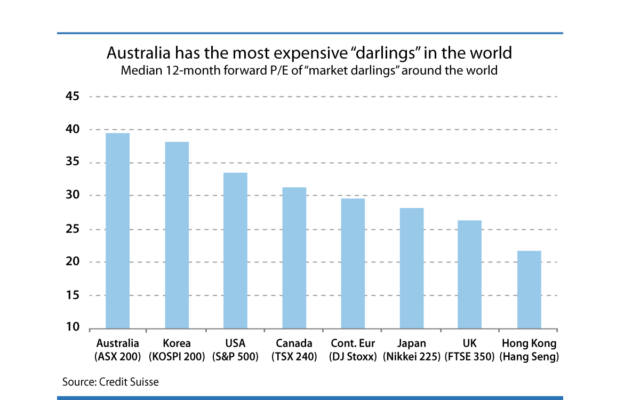

Australia is home to some of the most expensive market darlings in the world, and they have never been more expensive relative to the market – apart from at the peak of the dotcom boom in the mid to late 1990s.

Not only do some of Australia’s market darlings trade at a premium to their international peers but they also trade at a premium to their predecessors.

The Australian market index is heavily weighted towards old-economy businesses such as the big four banks and major miners. Therefore, due to the small number of high-quality growth companies (namely technology stocks) in our market, investors are willing to pay big multiples for their prospective earnings.

Current market darlings include Altium Ltd (ALU), Appen Ltd (APX), REA Group Ltd (REA), Technology One Ltd (TNE) and Wisetech Global Ltd (WTC).

These current darlings are high-quality businesses, exuding strong financial health scores (as per their financials), generating high amounts of return on equity and consistently reporting above market earnings-per-share growth. However, at current valuations the risk-reward trade-off simply does not make sense for a prudent long-term investor.

Over the past decade, we have experienced a low-growth environment, with the US Federal Reserve and other central banks all embarking on quantitative easing and negative real-interest-rate policies to spur economic growth. Consequently, asset values globally have risen to excessive levels after central banks have flooded the markets with easy money and investors were forced into growth assets to meet their return objectives. This has been one of the key drivers underpinning some of the current valuations for the market darlings.

Not only do some of Australia’s market darlings trade at a premium to their international peers but they also trade at a premium to their predecessors.

However, with the Fed looking to normalise monetary policy settings on the back of strong US data points, this may create a headwind for market-darling valuations going forward. When using a discounted cash flow (DCF) to value high-growth companies, a higher discount rate (i.e. interest rate) will have the effect of reducing the present value of future cashflows, thus ascribing a lower valuation (all things being equal).

Empirical research has proven that over the long term the market consistently rewards investors who focus on stocks with certain quantitative attributes such as low price-earnings, price-to-cash flow, and price-to-sales ratios.

Investors with a blatant disregard for valuation are enamoured by the narrative and willing to pay up to 100 times for a company’s earnings; and are then consistently punished over long periods of time and over many market cycles.

James Montier, a respected value investor, writes: “This is the world of behavioural finance, a world in which human emotions rule, logic has its place, but [stocks] are moved as much by psychological factors as by information from corporate balance sheets … They fail to produce predications that are even vaguely close to the outcomes we observe in real financial markets … what causes [stocks] to deviate from their fundamental value. The answer quite simply is human behaviour.”

As long as humans remain irrational, we will continue to observe with caution the rise and fall of the market darlings.

Adam Spicer is a financial adviser

with Baillieu.

comments