‘You have to be able to talk about it’

To mark International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, we speak to Naomi Tucker, a changemaker in the Jewish domestic violence space ahead of her Australian visit

IT was 27 years ago when Naomi Tucker attended a conference held by the National Coalition against Domestic Violence. She had been working in shelters for battered women at the time, and decided to go along, curious to join the Coalition’s Jewish women’s caucus.

“I had never thought about doing this work in a Jewish context or with my Jewish identity – they were two separate things for me. At this conference, women were talking about what it meant to do this work as a Jew,” Naomi recounts from her home base in the San Francisco Bay area.

It moved her, and much to her surprise, at the end of the conference, Naomi was approached to chair the caucus. She declined, believing that she didn’t have enough real experience in working with Jewish survivors of domestic violence. Her refusal was not accepted.

“So I said, I would do it only if I could have broader input. I need many more voices than mine,” she shared, and then organised a meeting of everyone she knew who worked in the field and happened to be Jewish.

Around her kitchen table, Naomi posed the question, “What do you think should be on the national agenda?”

The answer was unanimous, she tells.

“We don’t care about your national agenda. We care about why no one is talking about domestic violence here, in the Jewish community. Let’s do something about that.”

On that day, the group of women wrote a mission statement that today remains the mission statement of Shalom Bayit – the organisation Tucker co-founded with the aim to foster the social change and community response necessary in order to eradicate domestic violence in the Jewish community.

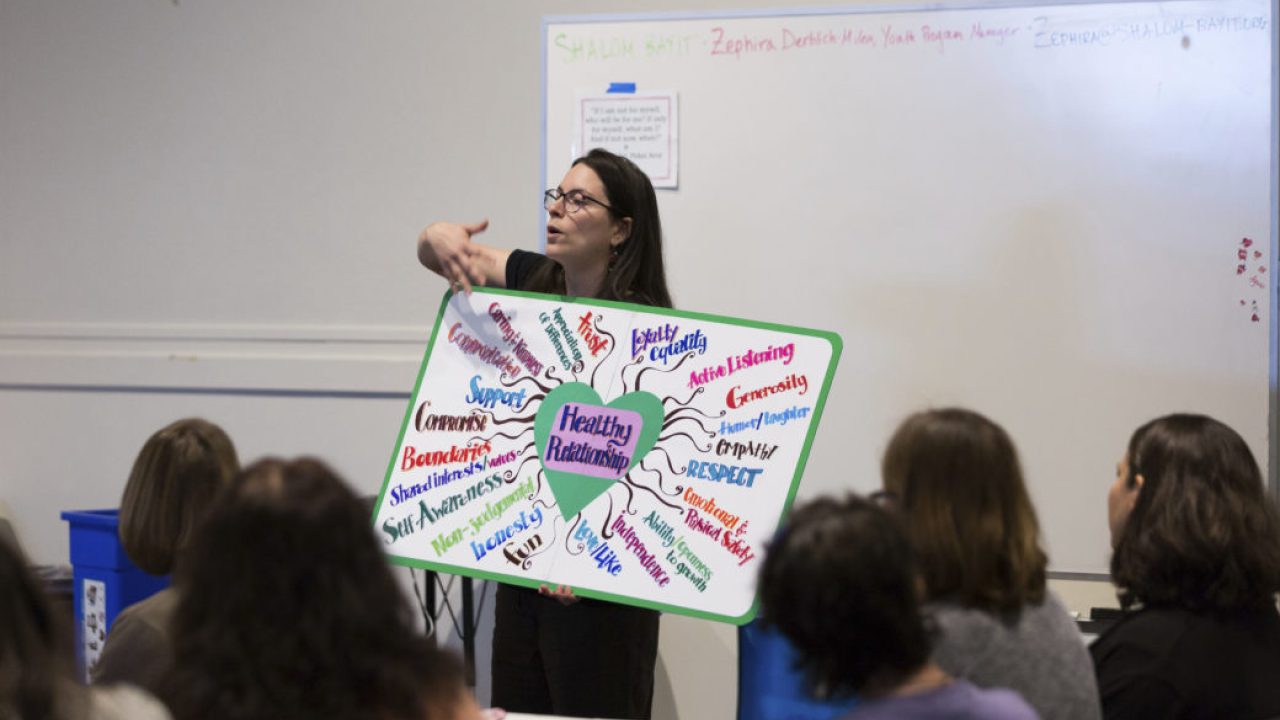

EACH year, Shalom Bayit assists around 100 domestic violence survivors in the Jewish community of the San Francisco Bay area. Aside from providing support, counselling, safety planning and advocacy to Jewish women, the organisation is strongly committed to education and abuse prevention, and facilitates panels and workshops in the Jewish community, in-service training sessions for rabbis and other communal professionals.

Youth education is also a major focus, with healthy relationships and consent workshops, dating violence prevention programs and companion programs for parents and Jewish educators delivered to over 15,000 Jewish primary, high school and college students and their parents and advocates. Shalom Bayit also established a rabbinic advisory council, a group of 90 interdenominational rabbis who came together to support the organisation, and meet yearly to discuss domestic violence and how they are tackling the issue from the pulpit and with congregants.

But the support of the community and the success of Shalom Bayit was not garnered overnight, with Naomi commenting the climate for discussion has “changed tremendously over the last two-and-a-half decades”.

“When we started, we could not even get any Jewish organisation or synagogue to let us borrow a meeting room for an hour, let alone come and speak,” she says.

“When I would call, people would say, ‘What did you say? Domestic violence? Oh no. We don’t have that problem here.'”

The early years were about knocking on doors, trying to figure out with whom they could connect to find a platform opening the conversation – “because we believed that once we did, we would really break the silence, and women in particular would be hungry to have our support and to talk about it with us.”

She was right. First, the Jewish women’s organisations came on board, later the clergy, and eventually Jewish day schools.

“But it literally was knocking on doors, and begging for attention for a long time,” Naomi adds.

Reflecting on the stigma of bringing domestic violence out of obscurity, Naomi notes two great challenges the organisation has encountered.

“[There] is the deep cultural belief that we don’t have a problem here,” an idea Naomi postulates is rooted in our history as a response to the threats the Jewish people have traditionally faced from the “outside” world, “but whenever we create home, that is where there is peace”.

The notion extends that women held the responsibility for keeping the peace at all costs – even if just presenting the image of a peaceful home.

“This concept of Shalom Bayit has sort of created a myth in the Jewish community that we have perfect homes and perfect families,” says Naomi.

The other challenge, she continues, is that most abuse occurs behind closed doors with no witnesses between the two people who are usually known in the community – “and community leaders or clergy are hesitant to address something publicly because they might be friends with the abuser, or they can’t imagine that person behaving that way”.

Irrespective of the discomfort, Naomi continued to push for dialogue.

“You have to be able to talk about it because that is the only thing that will actually stop this from happening in our own community.

“So often, we have seen women’s safety put at the bottom of the totem pole of Jewish communal priorities … [It needs to be put] on our Jewish social justice agenda, as a communal priority. We work on so many justice issues in the community, and most of the time they don’t include women – yet women are half of our population.

“That has to shift.”

ONE in four women in the US will experience abuse from an intimate partner in their lifetime, a statistic Naomi explains is no different for the Jewish community.

Closer to home, the Australian Jewish community is not dissimilar. It is also estimated that one in four women have experienced physical violence by an intimate partner, and 25 per cent of women have experienced emotional abuse from a current or previous cohabiting partner.

With formal research lacking in the prevalence of domestic violence specific to the Jewish community, “We know generally-speaking that rates of family violence in multicultural, diverse and faith-based communities reflect that of the broader community,” confirms a statement from Jewish Care Victoria.

Manager of Jewish Care Victoria’s Individual and Family Services Marilyn Kraner reveals that in the past financial year alone, one quarter of all referrals to the social work team were for matters related to family violence and family discord.

Meanwhile, since the commencement of this financial year, the number of cases that have involved high risk matters including involvement of police, child protection and courts appear to have increased even further.

As for JewishCare NSW, around 40 families each year are assisted with domestic violence matters.

“Some of these involve a huge amount of work and support including accommodation, schooling, legal issues as well as financial support,” added a JewishCare NSW statement.

These are the reported cases.

According to Naomi, the nature of abuse in the American Jewish community is not differentiated, although, she adds Shalom Bayit often works with a highly educated, professional population, and in these groups, “we tend to see more sophisticated verbal and emotional abuse – but there is not necessarily less severity or frequency or different types of abuse in Jewish populations”.

Regardless of the type of abuse, the number one piece of advice Naomi urges to those who are experiencing domestic violence is to ensure they can talk about it confidentially.

“That is so important, just to have a place where they can feel heard, and believed and validated … because part of the abuse is that brainwashing component of making the victim feel like everything is their fault,” she says, also encouraging the victim to reach out to a domestic violence expert who can help them put a safety plan in place.

“Also, be sure to do anything you can not to be isolated,” says Naomi, who explains that often the abuser will increasingly marginalise the victim, interfering in relationships with family, friends and community or encouraging their partner to quit their job or stop going to school.

“The more they do that, the more they have control over that victim and that victim has fewer avenues for support to help break that isolation.”

In the post-#MeToo world, Naomi also passionately advocates for the promotion of healthy Jewish masculinity, noting the social acceptance for “men to be in control or to express anger, but not okay for them to cry, or express vulnerability”.

Tackling the topic in Shalom Bayit’s youth programs, Naomi ensures Jewish texts and values are used to help combat sexist attitudes and be more allied to women. She probes the subtle messages of sexism represented in the community.

“Think about how many men are in control of Jewish organisations compared to women? Or when you have a board of directors or a committee with men and women on it?”

AFTER 35 years in the domestic violence space, nothing shocks Naomi anymore, but the stories that stay with her the most are those of impact she hears from women years after they have escaped from domestic violence situations.

Naomi recalls one woman whose rabbi told her that he thought her husband was being abusive towards her. The woman became angry and told the rabbi to get out of her business. She couldn’t believe he would say something so terrible about her husband, and did not speak to her rabbi for years after. When the woman finally left her husband years later, she poignantly told Naomi, “I think maybe that rabbi saved my life.”

“And so, I tell people, especially clergy, it is so important for you to name it when you see it. Even if that person isn’t able to take it in then.

“When they’re ready – whether that is in three days, or 10 years – they can pull those words out of their pocket, and you will be there with them to support them in that moment.

“Even if we only get one minute to tell someone this is what I see, or you don’t deserve to be treated that way, that is sometimes so incredibly important and life changing,” she says, citing the Talmudic words of Rabbi Tarfon, “It is not our job to complete the task, nor are we free to desist from it.”

“We can’t always save people from situations and I think this is the hardest part for family members and clergy. You can’t make someone leave a relationship or do what you think is the right thing, but you can plant a seed, and then be there when they’re ready.”

ON a personal level, it is impossible to work in the domestic violence sphere within one’s own community without it taking a toll, tells Naomi, who concedes if she didn’t have ways to care for herself, she would have burned out a long time ago.

“The cases that are harder for me are the ones in which we can’t get the leadership to do the right thing,” she says, continuing, “I think that, even though there are cases of very high danger and very high trauma, these ones that are most difficult for me personally, are when the abuser gets to roam free in their public Jewish communal role.”

How does she deal with that?

“I continue to advocate and be a loud voice – and I don’t give in,” she says after a long pause.

“My work at Shalom Bayit is a place to channel all the anger and frustration of the injustices of the world into something positive.

“That something positive is the change that I see in women’s lives on the ground, when they have created a new life for themselves, free of violence – and that is what keeps me going.”

Naomi Tucker will be speaking at the Preventing Violence Together Community Breakfast held by Jewish Care Victoria together with Unchain My Heart and the Glen Eira City Council on Tuesday, December 3 from 7.30am-9am.

To book, visit jewishcare.org.au/pvt.

If you are in immediate danger from domestic violence, call 000. For additional support, call:

Jewish Care Victoria: (03) 8517 5999

Jewish Care NSW: 1300 133 660

1800 RESPECT: 1800 737 732

Safe Steps: 1800 015 188.

Get The AJN Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

comments