THE Israeli spacecraft Beresheet (“Genesis” in Hebrew) took off on February 22, 2019 from Cape Canaveral, carried on a Falcon 9 rocket from entrepreneur Elon Musk’s SpaceX, bound for the moon.

Complete with a plaque installed on the outside of the lunar lander with the Israeli flag and the phrases “Am Yisrael Chai” (the people of Israel live) and “Small country, big dreams”, it was hoped Beresheet would make history as both the first private-sector landing on the moon, and the first craft from Israel to reach it.

Unfortunately, a technical glitch caused the craft’s engines to fail as it approached the lunar surface, and though engineers were able to restart them, it was too late and Beresheet crashed into the moon at 500 kilometres an hour.

“We were very close to the moon,” operation control director Alex Friedman said to engineers in the SpaceIL control room near Tel Aviv after communication with the spacecraft went down.

An unfortunate ending to a long, amazing, historic journey: @TeamSpaceIL's Beresheet did not land successfully on the Moon. We applaud everyone who worked on this project on the their achievement.

And of course, if at first you don't succeed, try, try again! #IsraelToTheMoon pic.twitter.com/M4K64PeBDc

— Embassy of Israel | #IsraelAt73 (@IsraelinUSA) April 11, 2019

“We are on the moon, but not in the way that we wanted to.”

But according to Israel Space Agency chairman Professor Isaac Ben-Israel, in one way at least, the $US100 million mission was not a failure.

“It was not 100 per cent successful … but still we got the main thing. There was not even one kid in Israel who was not talking about it,” he said during a webinar with Space Industry Association of Australia CEO James Brown last month.

“And it increased [by] a lot the number of kids in high schools that decided to take more seriously mathematics, sciences, et cetera.”

He expanded, “One of the driving forces behind Israeli activity in space was and still is education.

“We want to influence kids to take more seriously science. Research found there are three topics that attract the imagination of young kids and influence them to be more interested in science. One was space.”

Ben-Israel can personally vouch for this fact.

“In 1961, Israel launched its first rocket into space. Only the big powers at the time, the USA and the Soviet Union, had launched rockets into space by 1961,” he said.

“I was so much impressed by the news I decided to build my own rocket. This is how I was attracted to space when I was 10 years old.”

#OnThisDay two years ago all of Israel held its breath as #Beresheet 1 lifted off on its journey to the Moon. Soon, history was made, as the world's first private space craft entered the Moon's orbit.

It was an amazing experience for us, let us know how you remember the launch pic.twitter.com/E9Jq2ELsKr— Israel To The Moon (@TeamSpaceIL) February 21, 2021

ISRAEL’S wider space program began after the Camp David peace accord was signed with neighbouring Egypt. Like many of Israel’s technological advances, the program was born of tactical necessity.

“Part of the agreement was that the Sinai Peninsula will stay demilitarised. And we wanted to verify that the Egyptians were keeping their part of the agreement but we couldn’t send any more reconnaissance aircraft to verify,” Ben-Israel explained.

“The only way to do it was to use reconnaissance satellites. Therefore the same prime minister who decided to sign the peace agreement officially established the space agency and declared the first project of defence reconnaissance satellites. This was the first major step.”

But Israel faced a unique problem.

“We couldn’t launch satellites to the north, east or south. The only way we could launch our satellites, because of the geography of Israel, is into the Mediterranean Sea which is west,” he said.

“Earth is rotating from west to east. And if you launch westward it means you launch it against the rotation of Earth and you lose a lot of velocity, a lot of energy.”

He said the first thought to overcome this problem was to make the satellites smaller. But to be an effective reconnaissance craft, the aperture of its telescope needed to be large enough to produce images of a certain resolution.

“Therefore the only solution we found was to make it lighter,” Ben-Israel said.

Israel is returning to the Moon! Here is everything you need to know about #Beresheet2 ????????#IsraelToTheMoon pic.twitter.com/yxTLi0Bej6

— Israel To The Moon (@TeamSpaceIL) January 11, 2021

Using materials other than glass for the telescope lens, Israeli engineers successfully built a satellite that was much lighter than any other.

“The first family of reconnaissance satellites that we built was in terms of performance the best in the world, we had better resolutions at that time than everyone else, but lighter … around 300 kilograms,” he said.

“Once we had it, we gradually started to think about non-defence applications of the same technology. We found we have a relative advantage because there is a rule across all areas of technology, you pay by the weight,” he added, explaining that American satellites with similar capabilities weighed up to 10 times more.

“Which means you need a bigger launcher, which means you pay more here, you pay more there and at the end of the day it was much more expensive.”

Approached by France’s National Centre for Space Studies to collaborate on a lightweight environmental monitoring satellite, the Israeli agency agreed.

“We did it together and then we said okay, if we really do have some advantage here, let’s apply it to other fields,” Ben-Israel said.

“You take the same satellite and you can sell images for the requirements of the civilian society. But we started also to build communication satellites and today we do the whole spectrum.”

Photo: Haim Zach/GPO

The latest trend is the use of nanosatellites, which are not only much cheaper to produce but can be launched in multiples.

Israel’s first research nanosatellite, BGUSAT – a collaboration between Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel Aerospace Industries and the Israeli government – blasted off from India in February 2017.

A little larger than a milk carton, it was launched to track atmospheric gases in order to understand climate change, to examine changes in ground moisture that could indicate desertification and to monitor plant development in different regions.

Two months after BGUSAT’s launch, a nanosatellite built by Israeli high school students launched from Cape Canaveral to study the plasma density of Earth’s lower thermosphere.

“Then another high school did it, and two months ago, another eight [satellites] by high schools. This is now almost common by high schools in Israel, which put space into their curriculum because of the demand,” Ben-Israel said.

Meanwhile, Tel Aviv University’s first nanosatellite launched into orbit in February this year. AU-SAT1, which will conduct several experiments while in orbit, is the first nanosatellite to be wholly designed, developed, assembled and tested at an Israeli university.

A constellation of three more Israeli nanosatellites is due to launch from the US this month.

Space developments are happening on the ground, too. Earlier this year a team at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem discovered the first evidence of radio flares emitted only long after a star is destroyed by a black hole using ultra-powerful radio telescopes.

Ben-Israel has observed an exciting change in space technology over the last decade.

“Until 10 years ago, most of the space activities were done by governments. Private industry was sometimes building something for the government, but the government determined their requirements and also budgeted projects,” he said.

“In the last 10 years, we have this so-called ‘NewSpace’ which means it’s going from the hands of the governments to be a more normal activity of civil society.”

In the “start-up nation”, this means there is no shortage of new ventures vying for a piece of the action.

One start-up, Ramon.Space, builds computer hardware that is resilient to radiation, extreme temperatures, zero gravity and vacuum, in order to withstand the harsh conditions of space. Its technology was used in Japan’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft, which landed in the South Australian outback in December last year, having recovered sub-surface particles from an asteroid.

Meanwhile a kibbutz-based start-up, Ricor Cryogenic and Vacuum Systems, created a system to cool the spectrometer on the Curiosity Mars rover.

“Some Israeli space start-ups have more ambitious missions in their vision like building satellites,” Ben-Israel said.

One such start-up began with plans to build a satellite that will push older satellites that are no longer used further into space to make room in orbit for new ones. That has now evolved into the idea of attaching small engines to the old satellites to move them.

“They just raised $US100 million a few weeks ago or something like this,” Ben-Israel said.

“Once it becomes cheap enough, then you can apply the whole start-up culture also to space.”

In the meantime, Israel’s moon dream is also still very much alive.

SpaceIL, in cooperation with Israel Aerospace Industries and the Israeli Space Agency, aim to launch a new craft in 2024.

“One of the messages that is important to education is even if you fail, it’s not a reason to stop your activity,” Ben-Israel said.

“We don’t want the second one to be a repetition. We will have to do something that again attracts the attention of imagination of young kids, not only in Israel, but kids all over the world.”

The new craft will comprise an orbiter which is planned to circle the moon for years, while two landing modules will touch down on different parts of the moon.

“By this we will increase our chance of a soft landing and each one of them will make a different mission,” he said.

“The missions will be a mix of scientific and also symbolic missions … that will again attract the imagination of young generations.”

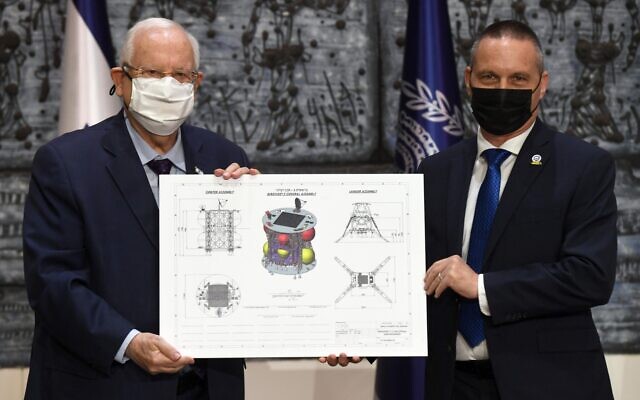

Launching the project in December last year, Israeli President Reuven Rivlin said it “will extend the boundaries of human knowledge with groundbreaking scientific experiments, helping us to understand better the universe in which we live”.

SpaceIL CEO Shimon Sarid said the Jewish State was “aiming high … not just to outer space, but to the long-term future of the State of Israel.

“We will do it by raising curiosity and hope, the ability to dream and realise, and through strengthening technological education, research, science and engineering for Israeli students.

“By doing so, we will ensure Israel’s technological mobility for today’s schoolchildren who are tomorrow’s scientists and engineers.”

WITH THE TIMES OF ISRAEL

comments