Just Josh

Treasurer, deputy Liberal leader and top Jew in the country Josh Frydenberg shares a more personal side of his life with Rebecca Davis.

Treasurer, deputy Liberal leader and top Jew in the country Josh Frydenberg shares a more personal side of his life with Rebecca Davis.

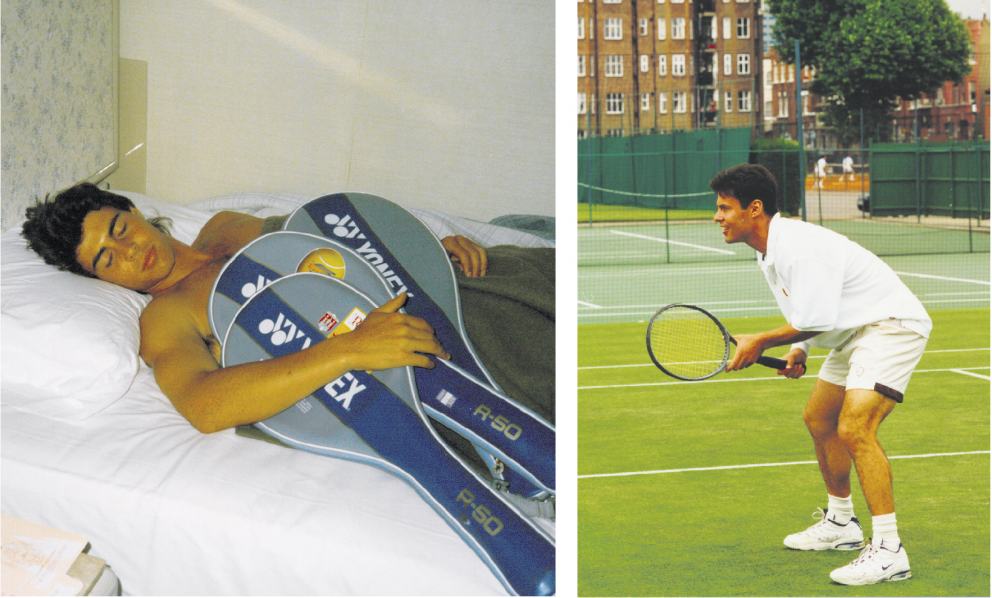

WHEN Josh Frydenberg enters the room, he does so with purpose. While his commanding presence is larger than his stature, it is balanced against a measured warmth. He offers a coffee as he leads the way to his office in his electorate of Kooyong. The walls are adorned with tributes to his sporting and political heroes, and mementos from his tennis days, which he proudly shares.

He is the Treasurer of Australia, and the deputy leader of the Liberal Party; the man many have predicted as a future prime minister.

But this morning, his mind is occupied by matters closer to home.

“I was a bit late because I was sitting having peanut butter toast and playing cubby houses with my son and looking at drawings with my daughter,” he explains.

“We were looking for treasure through the house that pirates might have left.”

The Treasurer looking for treasure.

The irony is telling – illustrative of his values as a loving family man – but in the world of federal politics, it can be a delicate balancing act.

“Last night, I arrived from Sydney. We came straight from the airport but I got home at 11 o’clock, so the children were fast asleep.

“Tonight I’ve got a dinner, so I won’t see them, and tomorrow morning I’m on a plane, so I won’t see them then,” he shares solemnly.

They are his “two bundles of joy”.

“People say to you, only when you have a child do you realise what it means to have a degree of emotion and love. You don’t really appreciate that until it happens and you just love the kids,” Frydenberg kvells.

He tells of his love of weekends with Gemma and Blake, and special mornings during the week when he can take his daughter to school. It is a semblance of normalcy in a frantic life that is “tough on families”, he muses.

But he promptly credits his “incredibly supportive and loving” wife, Amie.

“She takes it all in her stride, and she has allowed me to be able to do what I want to do, and I have to say without her, and her support, I wouldn’t have been able to undertake this role.”

The importance of family has been instilled in Frydenberg from a young age.

He was born in Melbourne in 1971, with both sets of grandparents having migrated to Australia from Europe.

Arriving in the late 1930s, paternal grandparents Morrie and Leah – or “pappa-daddy and nanny” – were like many Jewish immigrant families of that time, and “started with nothing”, he tells.

Morrie began work on the docks fixing naval vessels during the war, but later went into the shmatte trade, opening four haberdashery stores with his cousins in regional Victoria.

Frydenberg would sometimes go with Nanny, to tend to the stores. He reminisces on the time they stayed at a pub in Colac.

“I remember my grandmother packing up the back of the Kingswood, and she would have to go to one store, while my grandfather would go to another.”

Frydenberg’s maternal grandparents, Sam and Ethel Strauss and their young children, including his mother Erica, were not able to leave their native Hungary until after the war. They were interned in the Budapest ghetto by the Hungarian fascists, and eventually made their way to Australia via displaced persons camps.

In his maiden parliamentary speech in 2010, Frydenberg honoured their story, and the family members that did not make it out of Europe, sharing that his great-grandparents, and many relatives on both sides perished in the Holocaust.

Frydenberg has never publicly shied away from the Jewish identity he calls “absolutely critical”.

“It’s been central to my upbringing and it has shaped the values that drive me today – family, learning, justice and importantly, learning from history.”

In 2015, Frydenberg attended the commemorative ceremony for the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau at the site of the camp, “one of the most moving experiences of my life”, he reflects.

Following the visit, he penned an opinion piece for The Australian.

“My family’s history is in many respects no different to that of so many other Jewish families who have their origins in Europe. Two of my great-grandparents and three great-aunts were killed by the Nazis as they came off the transport trains at Auschwitz,” he wrote.

“But from my first step until my last I felt empty, finding it hard to fathom what had actually taken place. No anger, just disbelief, as I listened for the voices from my family’s past.”

Australia offered the opportunity for a new start for the Strauss and Frydenberg families.

“My grandparents on both sides worked hard, determined to give their children a better start in life.”

Indeed, they did. Frydenberg’s mother, Erica Strauss became a psychologist, while Harry Frydenberg embarked on a career as a surgeon – “both leaders of their fields in their own rights”.

“I had a wonderful life growing up, and I’ve always felt hugely supported by two loving parents, and I have a great relationship with my sister.

“I have learnt a lot from my mother that helps me in politics. When I was a kid she gave me a sign for my door that said ‘The pain of disappointment is far easier than the pain of regret’.”

And there were also no regrets when after years of playing AJAX football, Frydenberg tried his hand at tennis as a young teen.

“My dad would hop on the court with me and take me to tournaments, and when I would go for a run in the morning, he would ride the bike next to me at 5.30am. But he never pushed me.”

Besotted by his new sport, Frydenberg wanted to leave school at Mount Scopus College behind and chase his dreams on the court. He persisted through HSC, and only once he was offered a place in a law and economics degree at Monash University did he decide to defer in order to focus on tennis. He played in Switzerland, Germany and Queensland, and later, several Maccabiah Games in Israel.

But by the end of the year, the experience came with a harsh realisation.

“My ambitions were greater than my talent,” he admits.

After Frydenberg began his university studies in 1990 he soon had his first taste of politics. Undeterred by an unsuccessful bid to become a school captain, he ran for a few positions on the student representative council, then achieved the position of president of the Law Students Society.

“There were certain things that I thought needed to be done at the university and at the law school in terms of advancing the interests of students and promoting opportunities for them to do clerkships.”

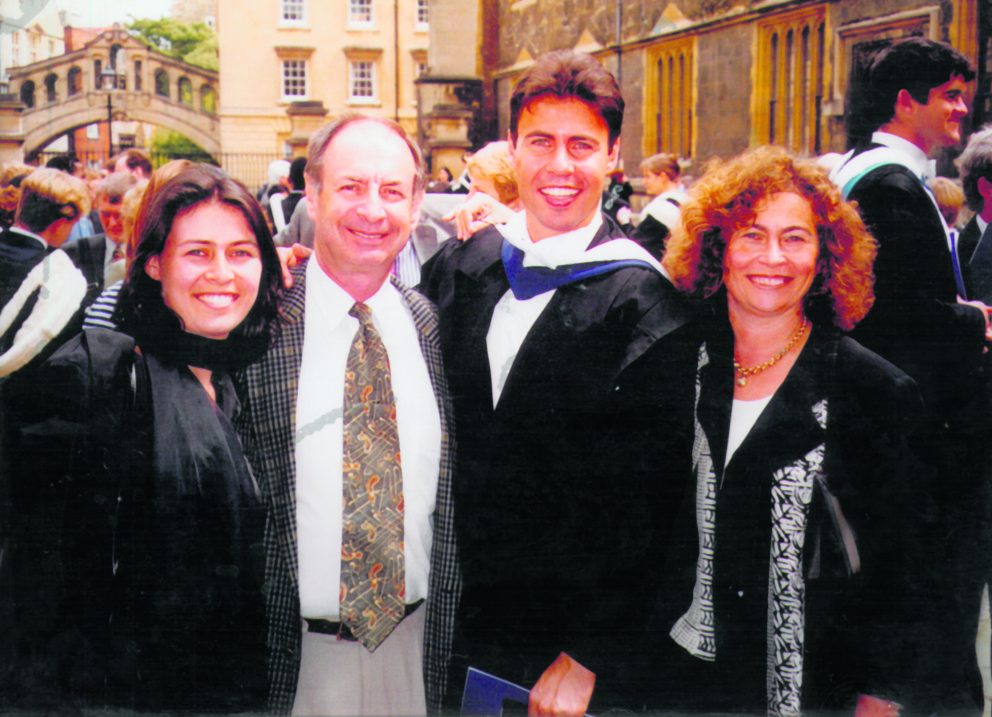

He began working on his articles at law firm Mallesons Stephen Jaques, but inspired by Chariots of Fire – a film he watched “at least 30 times” – Frydenberg applied for various international university scholarships. He was awarded both a Fulbright scholarship to the United States, and a Commonwealth scholarship to Oxford University in the United Kingdom.

Unable to decide which place to take, Frydenberg hopped on a plane to give both opportunities a go. First stop; Yale.

“The campus is wonderful, and sort of Gothic – but Newhaven is not exactly downtown Manhattan,” he recounts.

Despite this, he was “nearly sold” on Yale, but still felt it important to investigate Oxford.

“So, I get into London, and then you take a bus – it’s called the Oxford Tube. I step off the bus and onto those amazing cobblestones. I see these buildings and am blown away.”

Frydenberg immediately searched for a telephone box. He had to make a call to his good friend and mentor – Sir Zelman Cowen.

“So, I ring Sir Zelman, and I say I’ve just arrived in Oxford. This is where I’m meant to be. This is where I want to be. And he said, ‘fantastic’.”

Frydenberg studied at Oxford from 1996 to 1998 and completed a Masters of Philosophy degree in international relations, before returning to Australia to be admitted as a barrister and solicitor.

It was then he entered politics. The following year, he began as an assistant adviser to then attorney-general, Daryl Williams. He later served as senior adviser to foreign minister Alexander Downer.

“I learnt a lot working for him and got to travel to some really interesting countries around the world including Iraq and Iran. They were fascinating.”

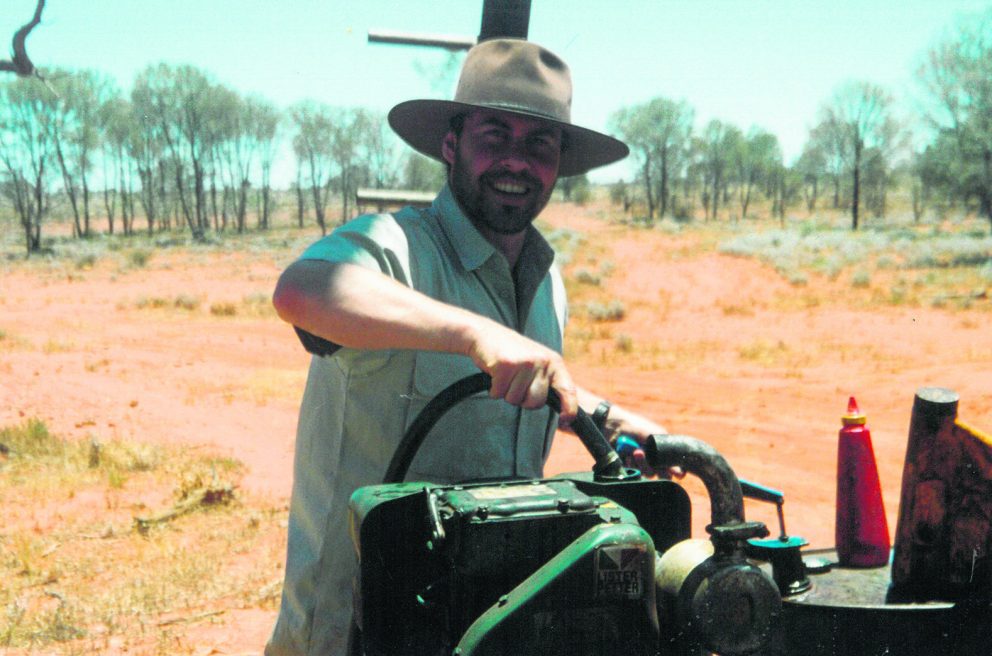

After four years with Downer, Frydenberg became senior adviser to prime minister John Howard from 2003 to 2004. But then he made a slight diversion from Canberra, leaving his role to spend a month as a jackaroo on a sheep station in South Australia.

In 2006 he ran for pre-selection in Kooyong against Petro Georgiou.

“I lost really badly,” he recalls. “But I picked myself up and ran again.”

Frydenberg successfully became the member for Kooyong in 2010, and has held the seat ever since.

“I learnt the importance of hard work and giving back to your community and that is what I am doing as a politician.

“Determination is absolutely key in every career path. Unless you are determined then you won’t achieve your potential.”

He pauses thoughtfully. “Sir Zelman always used to say to me, ‘Josh, what’s next? You’ve done this. Now get on to the next thing, and the next thing, and the next thing. You don’t need to take too much time to smell the roses. Just get on with it’.”

Frydenberg’s friendship with Sir Zelman had developed over time, and they met almost every weekend for breakfast over a decade.

So, what keeps Frydenberg motivated to “just get on with it” today?

“To create a better Australia for my children – and for my local community.

“I think it’s important to note Australia’s place in the region: how we capitalise on the opportunities that have been created, and the importance of being culturally and politically aware of the diversity of the nations on our doorstep.

“I see the future through my children’s eyes and the importance of leaving for them a better and stronger Australia. And I just see my role as Treasurer, and as deputy leader, is to do my bit in that much bigger picture.”

comments