The forgotten man remembered

Celebrating the centenary of the “Man from Africa” who saved Jewish orphans from Eastern Europe.

IT is said in the Talmud that “He who has saved one life it is as though he has saved the entire world”. Well, today there are many thousands of Jews around the entire world – some in Sydney, Melbourne and Perth – who are only alive today because of one man – Isaac Ochberg.

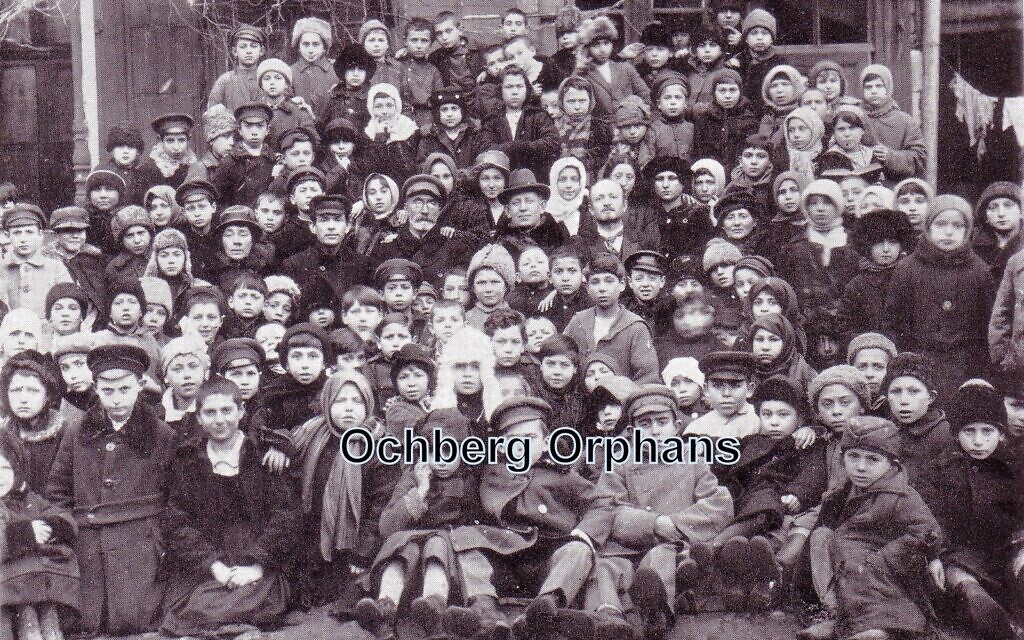

And yet, too few have heard of this Ukrainian-born South African businessman and philanthropist, who singlehandedly in 1921, rescued 187 Jewish orphans from war-torn Eastern Europe.

If a coronavirus pandemic threatens the world’s population today, one hundred years ago it was the disease of typhoid that threatened the lives of some 400,000 Jewish orphans in Eastern Europe. Not only typhoid but also a far more lethal disease seemingly devoid of any cure – antisemitism.

Pogroms were rife in the wake of the Russian Revolution, where a bitter civil war raged between the Bolsheviks and their Red Army and the reactionary White Army. The year 1921 was a dangerous time – it was hunting season with the prey Jews and the most vulnerable – Jewish orphans. With letters of their plight smuggled out from this war-torn region, one miraculously found its way to Cape Town, South Africa where even more miraculous, the cause was embraced by one man Isaac Ochberg – to save as many Jewish orphans as possible and bring them safely to South Africa.

On the 14th of March 2021, the centenary of this heroic rescue will be celebrated online, hosted by the South African Jewish Report and organised by the Isaac Ochberg Heritage Committee (Israel) in partnership with the Megiddo Regional Council. A panel debate on the saga with be moderated by host Howard Sackstein which will be followed by a ceremony from Megiddo in which all are invited to attend.

Celebrating the centenary, follows the inauguration in 2011 in the Megiddo region of the Isaac Ochberg Memorial Park, near Kibbutz Ein Hashofet, where its most moving feature is ‘The Hill of Names’. There, embedded in its rock and masonry are the plaques with the names of all the orphans “Daddy Ochberg” saved and brought to South Africa.

If the ceremony took a while to commence back in 2011, it was only because people could not tear themselves away from the ‘Hill of Names’ as each family crowded around “their” plaque of their ancestor. On that blistering mid-summer day, the tears could have irrigated the dry, thirsty land of Ramot Menashe on which the park is located. One such person was an Australian, who joined the long line of speakers who came to the microphone to tell their story. Arnold Nadelman from Melbourne, who had been adopted by the Nadelman family in Johannesburg as a child, was one of the last to speak and the last to have registered for the event. He had never known anything about his biological parents!

So overcome with emotion, Arnold found it difficult to speak but with his wife beside him – also in tears – he began. Only a week earlier, Arnold had never heard of Isaac Ochberg. Enjoying a shower in his bathroom, he heard his wife scream from the living room. Grabbing a towel, he joined her at their coffee table where he found her staring at a 1921 photo of orphan children in an article advertising the 2011 Ochberg reunion in The Australian Jewish News. Pointing at one child, she said:

“Arnold, that looks exactly like you as a child! How is this possible?”

They called David Sandler in Perth, who had recently published his monumental work: ‘Ochberg Orphans – and the horrors from where they came’. A quick investigation revealed that his father had been one of the 187 orphans and had been adopted by the Nadelman family. Arnold’s life was immediately put on hold as he and his wife hurriedly boarded a plane to Israel to join “my new family” in honouring “Daddy Ochberg”.

To understand the times and “the hell” from where these orphans came, one has only to learn of how Ochberg orphan Harry Stillerman at the Oranje Orphanage in Cape Town lost half his arm. A band of Cossacks on horseback had come galloping into his shtetl, shot his parents in front of him, and when one of them was about to slash Harry with his sabre, the young boy raised his arm to protect himself. With one fowl strike, he severed Harry’s arm off at the elbow and left him to bleed to death in the mud. Five-year-old Harry survived and was found by Ochberg and brought to South Africa.

Another of the orphans was the late Fanny Frier, who would later become Chairlady of the Cape Jewish Orphanage. She recalled as an orphan in Brest-Litovsk, waiting for the “Man from Africa” to come. “We were told a man from Africa was coming to save us. He was going to take some of us away with him and give us a new home on the other side of the world.” She said they were so scared but when Ochberg appeared, “with his reddish hair and cheery smile, we all took a great liking to him and called him “Daddy”. He would spend hours talking to us, making jokes and cheering us up.”

Before leaving South Africa on his daring rescue of the orphans, Ochberg met and negotiated with then then South African Prime Minister, Jan Smuts, who set the maximum number of orphans to be rescued at 200. However, there were three conditions. They had to be “genuine” orphans with no living parent; they had to be under the age of sixteen and had to be physically wholesome – not missing any limbs. Ochberg immediately agreed to all three conditions but would later disobey all. Young Harry Stillerman with one arm severed at the elbow, was a case in point!

Transforming fiction into fact, Ochberg – like a benevolent “Pied Piper of Hamelin’ – had crisscrossed by train and horse-drawn cart, a region beset by Civil War and pogroms, plucking up orphans at cities, towns and shtetls. Had they not been rescued, the odds were, they would have perished.

Before he passed away in Cape Town, Alexander Bobrow, who accompanied the children to South Africa with Ochberg and whose son-in-law would be the late Aaron Klug, the 1982 Nobel Laureate for chemistry, related:

“so many children were found that we set up three orphanages. At first Pinsk was so isolated by the fighting that we were dependent solely on our own resources. We had neither beds, bedding nor clothes and I recall using flower bags to make clothes for the children.”

When typhus broke out in one of the orphanages, Bobrow relates how he had to walk through the streets as shells were exploding. Balachou, the notorious Ukrainian had descended on the city with his murderous marauders and the pogroms raged for nearly a week. Bobrow recalled how an old lady tried to pacify the terror-stricken children by calling out: “The Almighty will keep us and save us – Now repeat after me.”

Reporting on his progress of the rescue, Ochberg wrote:

“I have been through almost every village in the Polish Ukraine and Galacia and am now well acquainted with the places where there is at present extreme suffering. I have succeeded in collecting the necessary number of children, and I can safely say that the generosity displayed by South African Jewry in making this mission possible means nothing less than saving their lives. They would surely have died of starvation, disease, or been lost to our nation for other reasons.”

History sadly records that this was to be. Those that survived the horrors of the 1920s would have perished in the horrors of the 1940s.

Today, there are thousands of descendants of these orphans scattered all over the world who will join a global audience for the SA Jewish Report online reunion on the 14th March. Participating in this event will be the Mayor of the Megiddo Regional Council, Itzik Kholawsky, who is proud of Ochberg’s name and legacy so embedded with his region in Israel. While the park – a UNEASCO recognized biosphere reserve – is still a work-in-progress, the South African section with the ‘Isaac Ochberg Scenic Lookout Memorial’ and ‘Hill of Names’ stands complete, “and is a testimony to the tenant from the Tanach (Hebrew Bible) that “Whoever saves one life, it is as if he has saved the entire world”.

What is more, stresses Kholawasky, “was Ochberg’s vision and support for a future Jewish State at a time when it was still a dream. The bequest he left in 1937 through Keren Hayasod to KKL- JNF – the largest to date ever made by an individual – was used to acquire the land that became two of our large kibbutzim in this area, Dalia and Gal’ed, both established before Israel’s independence and by Jewish youth movements, and both absorbed survivors from the Holocaust – fulfilling Ochberg’s legacy of saving Jewish lives.” Is it little wonder as Kholawsky reminds that that much of this region was once popularly known as ‘Evan Yitzchak’ – Hebrew for the ‘Stone of Isaac”.

How appropriate it is that the Ochberg saga is solidly embedded in the topography of Megiddo that is rich in history and biblical prophecy – “May his name resonate here for all eternity.”

To register for the webinar, visit http://bit.ly/sajr82. For further information contact David Kaplan: hildav@netvision.net.il

David Kaplan is a founding member and present chairman of the Isaac Ochberg Heritage Committee (Israel) and a former chairman of Telfed, the South African Zionist Federation in Israel. Kaplan is a journalist and editor of a number of magazines in Israel.

Get The AJN Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

comments